What is the nature of sequencing data?

sequencing sanger illumina pacbio oxford nanopore

The 50s, 60s and the 70s

The difficulty with sequencing nucleic acids is nicely summarized by Hutchinson:2007:

- The chemical properties of different DNA molecules were so similar that it appeared difficult to separate them.

- The chain length of naturally occurring DNA molecules was much greater than for proteins and made complete sequencing seems unapproachable.

- The 20 amino acid residues found in proteins have widely varying properties that had proven useful in the separation of peptides. The existence of only four bases in DNA therefore seemed to make sequencing a more difficult problem for DNA than for protein.

- No base-specific DNAases were known. Protein sequencing had depended upon proteases that cleave adjacent to certain amino acids.

It is therefore not surprising that protein-sequencing was developed before DNA sequencing by Sanger and Tuppy:1951.

tRNA was the first complete nucleic acid sequenced (see pioneering work of Robert Holley and colleagues and also Holley’s Nobel Lacture). Conceptually, Holley’s approach was similar to Sanger’s protein sequencing: break molecule into small pieces with RNases, determine sequences of small fragments, use overlaps between fragments to reconstruct (assemble) the final nucleotide sequence.

The work on finding approaches to sequencing DNA molecules began in late 60s and early 70s. One of the earliest contributions has been made by Ray Wu (Cornell) and Dave Kaiser (Stanford), who used E. coli DNA polymerase to incorporate radioactively labelled nucleotides into protruding ends of bacteriphage lambda. It took several more years for the development of more “high throughput” technologies by Sanger and Maxam/Gilbert. The Sanger technique has ultimately won over Maxam/Gilbert’s protocol due to its relative simplicity (once dideoxynucleotides has become commercially available) and the fact that it required smaller amount of starting material as the polymerase was used to generate fragments necessary for sequence determination.

Sanger/Coulson plus/minus method

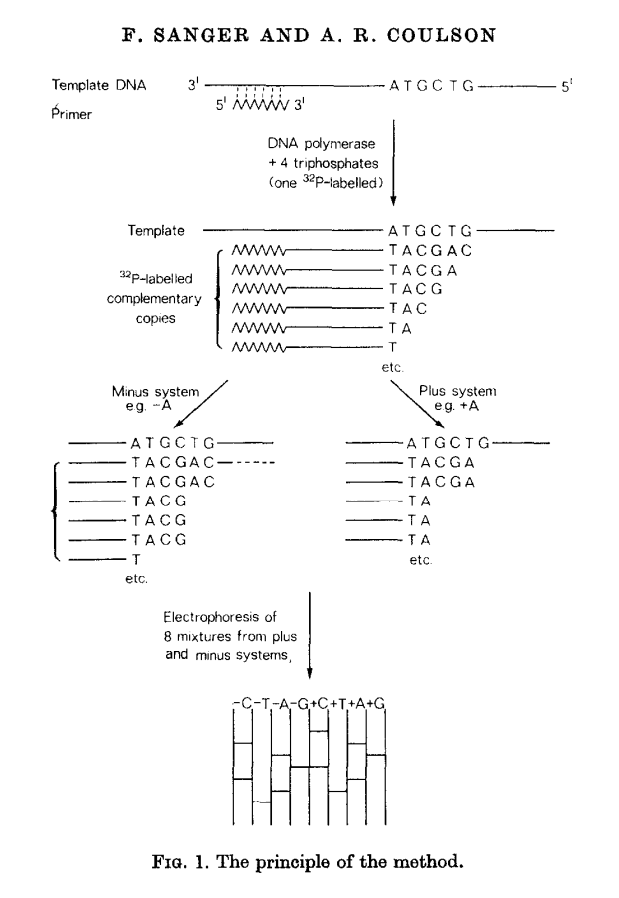

This methods builds on idea of Wu and Kaiser (for minus part) and on special property of DNA polymerase isolated from phage T4 (for plus part). The schematics of the method is given in the following figure:

|

| Plus/minus method. From Sanger & Coulson: 1975 |

In this method a primer and DNA polymerase is used to synthesize DNA in the presence of P32-labeled nucleotides (only one of four is labeled). This generates P32-labeled copies of DNA being sequenced. These are then purified and (without denaturing) separated into two groups: minus and plus. Each group is further divided into four equal parts.

In the case of minus polymerase and a mix of nucleotides minus one are added to each of the four aliquotes: ACG (-T), ACT (-G), CGT (-A), AGT (-C). As a result in each case DNA strand is extended up to a missing nucleotide.

In the case of plus only one nucleotide is added to each of the four aliquotes (+A, +C, +G, and +T) and T4 DNA polymerase is used. T4 DNA polymerase acts as an exonuclease that would degrade DNA from 3’-end up to a nucleotide that is supplied in the reaction.

The products of these are loaded into a denaturing polyacrylamide gel as a eight tracks (four for minus and four for plus):

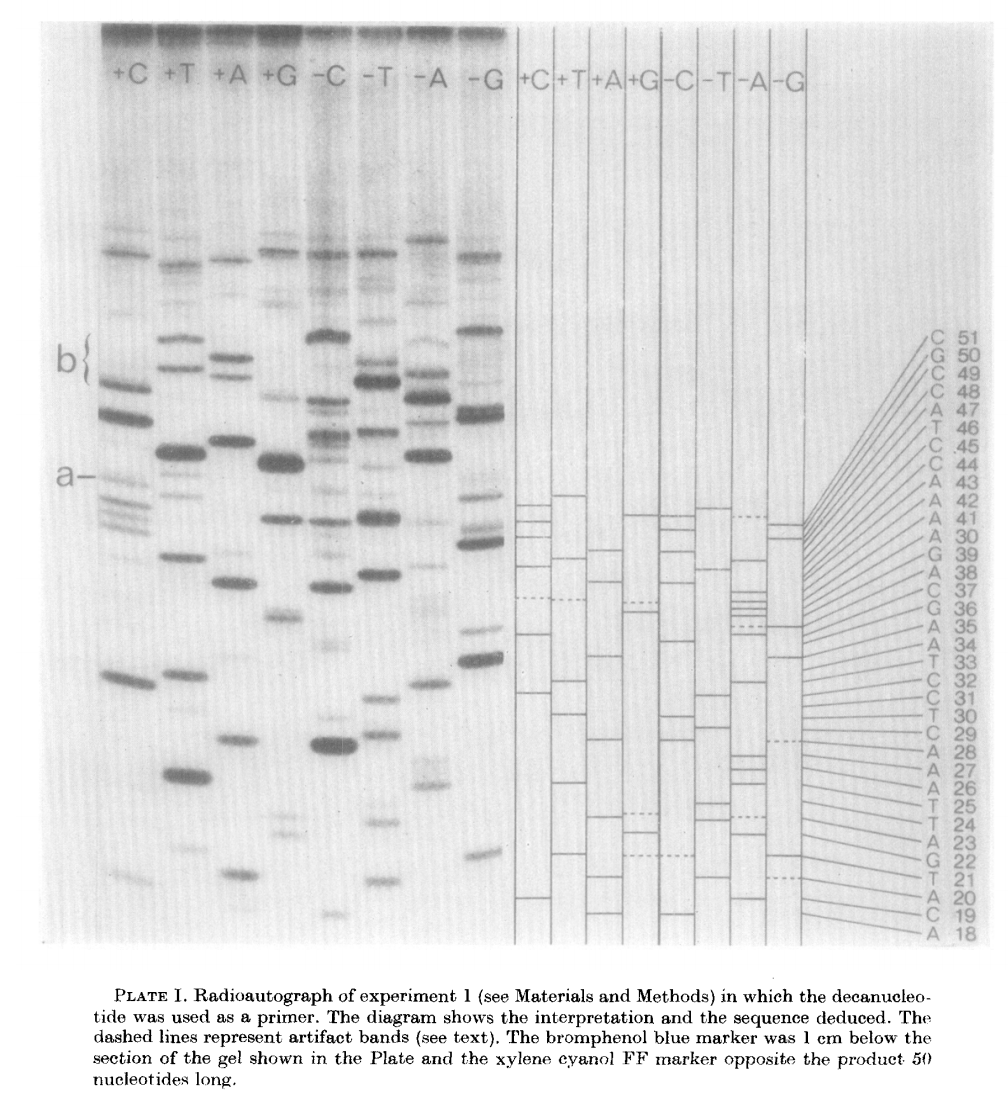

|

| Plus/minus method gel radiograph. From Sanger & Coulson: 1975 |

Maxam/Gilbert chemical cleavage method

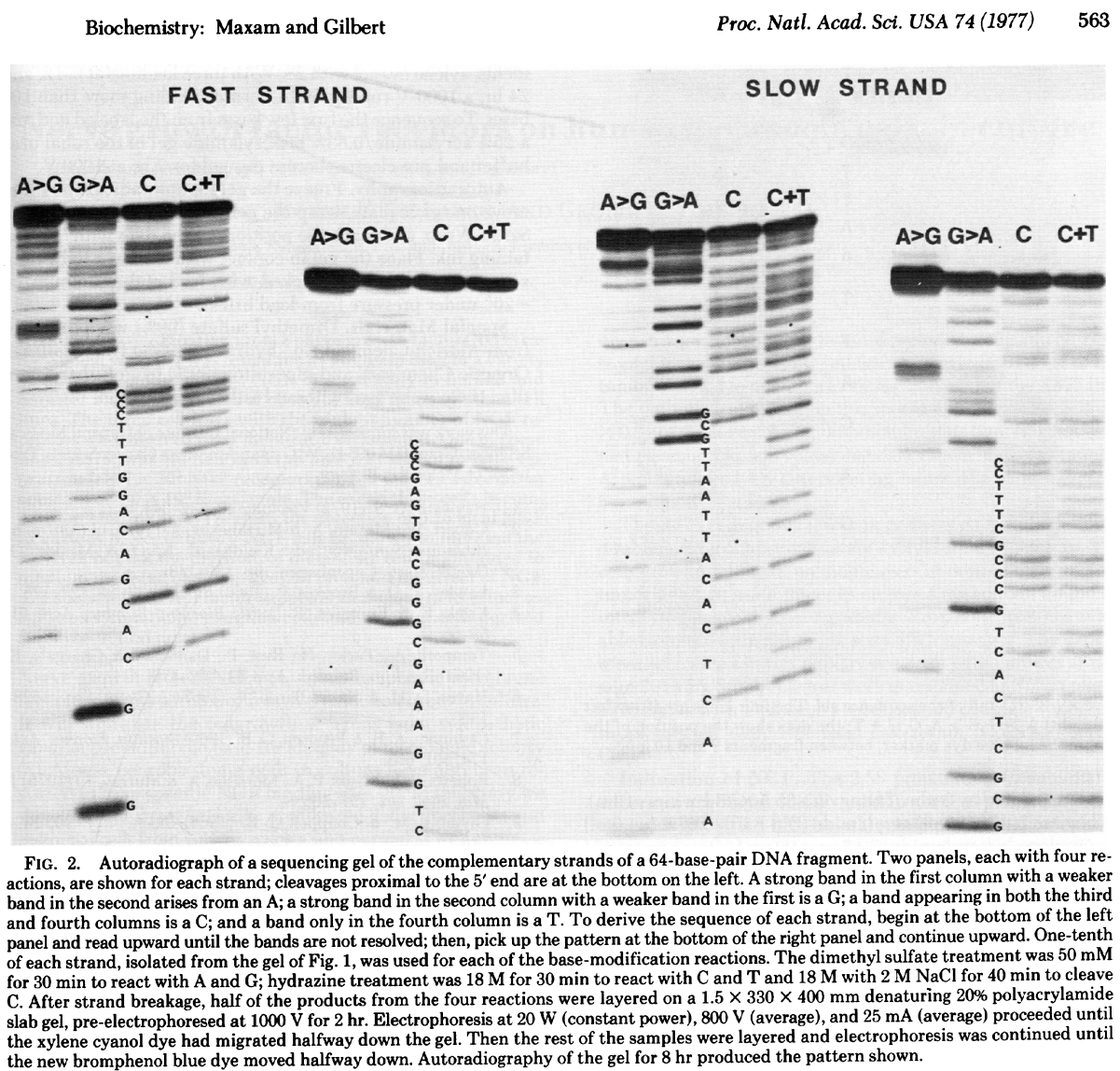

In this method DNA is terminally labeled with P32, separated into four equal aliquotes. Two of these are treated with Dimethyl sulfate (DMSO) and remaining two are treated with hydrazine.

DMSO methylates G and A residues. Treatment of DMSO-incubated DNA with alkali at high temperature will break DNA chains at G and A with Gs being preferentially broken, while treatment of DMSO-incubated DNA with acid will preferentially break DNA at As. Likewise treating hydrazine-incubated DNA with piperidine breaks DNA at C and T, while DNA treated with hydrazine in the presence of NaCl preferentially brakes at Cs. The four reactions are then loaded on a gel generating the following picture:

|

| Radiograph of Maxam/Gilbert gel. From Maxam & Gilbert: 1977 |

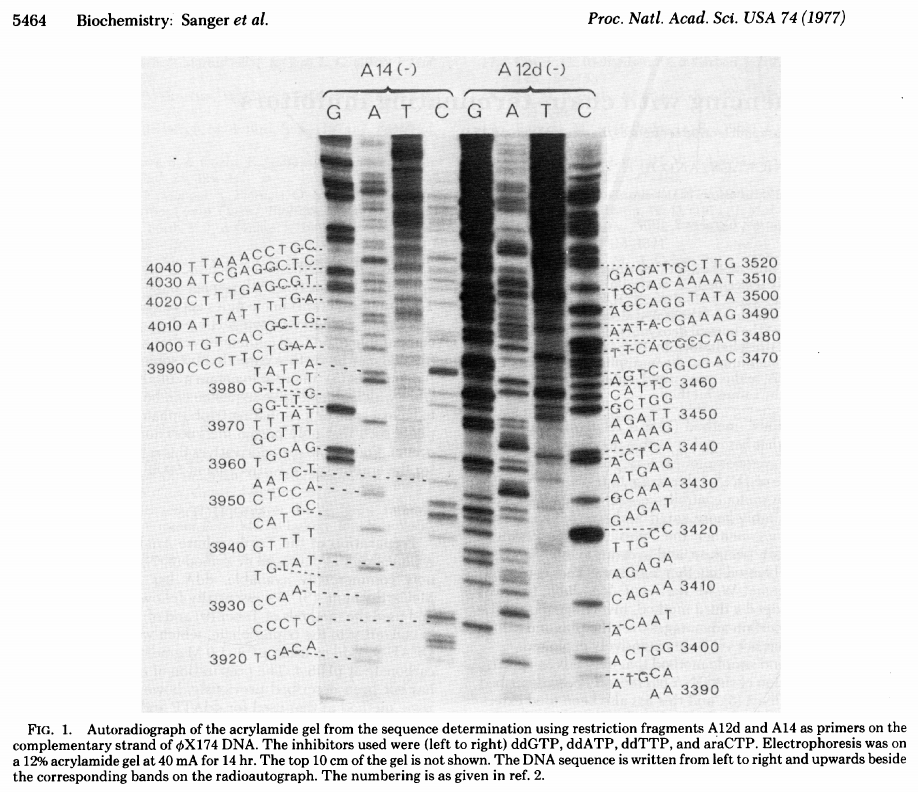

Sanger dideoxy method

The original Sanger +/- method was not popular and had a number of technical limitations. In a new approach Sanger took advantage of inhibitors that stop the extension of a DNA strand at particular nucleotides. These inhibitors are dideoxy analogs of normal nucleotide triphosphates:

|

| Sanger ddNTP gel. From Sanger:1977 |

Original approaches were laborious

In the original Sanger paper the authors sequenced bacteriophage phiX174 by using its own restriction fragments as primers. This was an ideal set up to show the proof of principle for the new method. This is because phiX174 DNA is homogeneous and can be isolated in large quantities. Now suppose that you would like to sequence a larger genome (say E. coli). Remember that the original version of Sanger method can only sequence fragments up to 200 nucleotides at a time. So to sequence the entire E. coli genome (which by-the-way was not sequenced until 1997) you would need to split the genome into multiple pieces and sequence each of them individually. This is hard, because to produce a readable Sanger sequencing gel each sequence must be amplified to a suitable amount (around 1 nanogram) and be homogeneous (you cannot mix multiple DNA fragments in a single reaction as it will be impossible to interpret the gel). Molecular cloning enabled by the availability of commercially available restriction enzymes and cloning vectors simplified this process. Until the onset of next generation sequencing in 2005 the process for sequencing looked something like this:

- (1) - Generate a collection of fragments you want to sequence. It can be a collection of fragments from a genome that was mechanically sheared or just a single fragment generated by PCR.

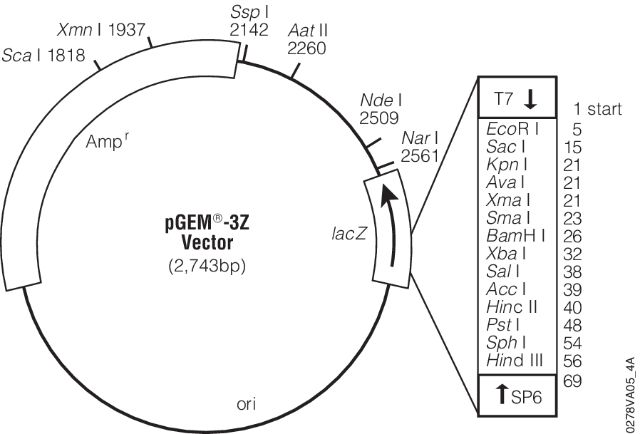

- (2) - These fragment(s) are then cloned into a plasmid vector (we will talk about other types of vectors such as BACs later in the course).

- (3) - Vectors are transformed into bacterial cells and positive colonies (containing vectors with insert) are picked from an agar plate.

- (4) - Each colony now represents a unique piece of DNA.

- (5) - An individual colony is used to seed a bacterial culture that is grown overnight.

- (6) - Plasmid DNA is isolated from this culture and now can be used for sequencing because it is (1) homogeneous and (2) we now a sufficient amount.

- (7) - It is sequenced using universal primers. For example the image below shows a map for pGEM-3Z plasmid (a pUC18 derivative). Its multiple cloning site is enlarged and sites for T7 and SP6 sequencing primers are shown. These are the pads I’m referring to in the lecture. These provide universal sites that can be used to sequence any insert in between.

|

| pGEM-3Z. Figure from Promega, Inc. |

Until the invention of NGS the above protocol was followed with some degree of automation. But you can see that it was quite laborious if the large number of fragments needed to be sequenced. This is because each of them needed to be subcloned and handled separately. This is in part why Human Genome Project, a subject of our next lecture, took so much time to complete.

Evolution of sequencing machines

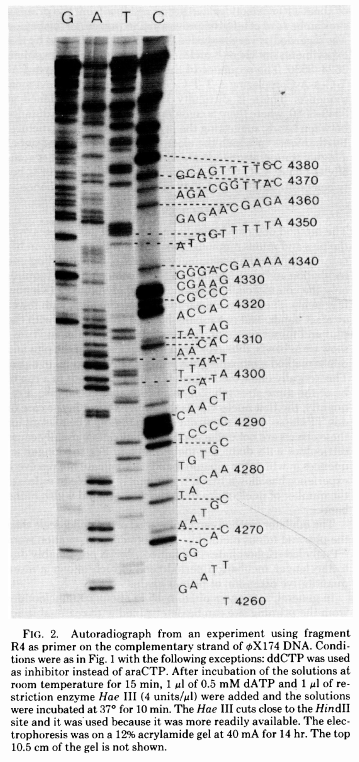

The simplest possible sequencing machine is a gel rig with polyacrylamide gel. Sanger used it is his protocol obtaining the following results:

|

| Figure from Sanger et al. 1977. |

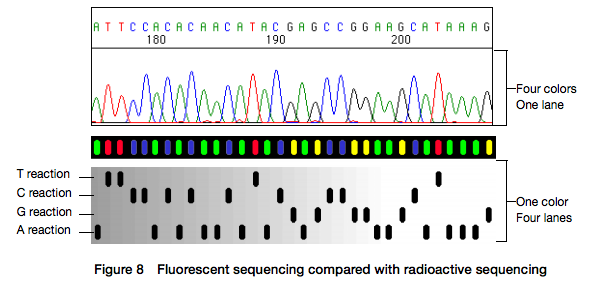

Here for sequencing each fragment four separate reactions are performed (with ddA, ddT, ggC, and ddG) and four lanes on the gel are used. One simplification of this process that came in the 90s was to use fluorescently labeled dideoxy nucleotides. This is easier because everything can be performed in a single tube and uses a single lane on a gel:

|

| Figure from Applied Biosystems support site. |

However, there is still substantial labor involved in pouring the gels, loading them, running machines, and cleaning everything post-run. A significant improvement was offered by the development of capillary electrophoresis allowing automation of liquid handling and sample loading. Although several manufacturers have been developing and selling such machines a de facto standard in this area was (and still is) the Applied Biosystems (ABI) Genetics and DNA Anlayzer systems. The highest throughput ABI system, 3730xl, had 96 capillaries and could automatically process 384 samples.

NGS!

384 samples may sound like a lot, but it is nothing if we are sequencing an entire genome. The beauty of NGS is that these technologies are not bound by sample handling logistics. They still require preparation of libraries, but once a library is made (which can be automated) it is processed more or less automatically to generate multiple copies of each fragment (in the case of 454, Illumina, and Ion Torrent) and loaded onto the machine, where millions of individual fragments are sequenced simultaneously. The following videos and slides explains how these technologies work.

Watch introductory video

NGS in depth

1: 454 sequencing

454 Technology is a massively parallel modification of pyrosequencing technology. Incorporation of nucleotides are registered by a CCD camera as a flash of light generated from the interaction between ATP and Luciferin. The massive scale of 454 process is enabled by generation of a population of beads carrying multiple copies of the same DNA fragment. The beads are distributed across a microtiter plate where each well of the plate holding just one bead. Thus every unique coordinate (a well) on the plate generates flashes when a nucleotide incorporation event takes plate. This is “monochrome” technique: flash = nucleotide is incorporated; lack of flash = no incorporation. Thus to distinguish between A, C, G, and T individual nucleotides are “washed” across the microtiter plate at discrete times: if A is being washed across the plate and a flash of light is emitted, this implies that A is present in the fragment being sequenced.

454 can generated fragments up 1,000 bases in length. Its biggest weakness is inability to precisely determine the length of homopolymer runs. Thus the main type if sequencing error generated by 454 are insertions and deletions (indels).

Slides

Video

Underlying slides are here

Reading

- 2001 | Overview of pyrosequencing methodology - Ronaghi

- 2005 | Description of 454 process - Margulies et al.

- 2007 | History of pyrosequencing - Pål Nyrén

- 2007 | Errors in 454 data - Huse et al.

- 2010 | Properties of 454 data - Balzer et al.

A few classical papers to start

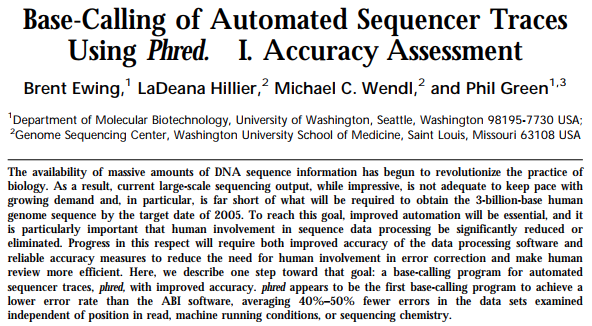

In a series of now classical papersp Philip Green and co-workers has developed a quantitative framework for the analysis of data generated by automated DNA sequencers.

|

|

| Two papers were published back to back in Genome Research. |

<hr>In particular they developed a standard metric for describing the reliability of base calls:

An important technical aspect of our work is the use of log-transformed error probabilities rather than untransformed ones, which facilitates working with error rates in the range of most importance (very close to 0). Specifically, we define the quality value q assigned to a base-call to be

$q = -10\times log_{10}(p)$

where p is the estimated error probability for that base-call. Thus a base-call having a probability of 1⁄1000 of being incorrect is assigned a quality value of 30. Note that high quality values correspond to low error probabilities, and conversely.

We will be using the concept of “quality score” or “phred-scaled quality score” repeatedly in this course.

Illumina

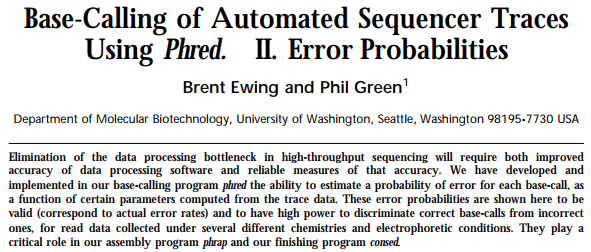

Illumina (originally called “Solexa”) uses glass flowcells with oligonucleotides permanently attached to internal surface. These oligonucleotides are complementary to sequencing adapters added to DNA fragments being sequenced during library preparation. The DNA fragments that are “stuck” on the flowcell due to complementary interaction between adapters are amplified via “bridge amplification” to form clusters. Sequencing is performed using reversible terminator chemistry with nucleotides modified to carry dyes specific to each base. As a result all nucleotides can be added at once and are distinguished by color. Currently, it is possible to sequence up to 300 bases from each end of the fragment being sequenced. Illumina has the highest throughput (and lowest cost per base) of all existing technologies at this moment. The NovaSeq 6000 machine can produce 6000 billion nucleotides in 44 hours. In this course we will most often work with Illumina data.

NextSeq two dye system:

|

| NextSeq uses two dye system. |

Slides

Video

Reading

- 2008 | Human genome sequencing on Illumina - Bentley et al.

- 2010 | Data quality 1 - Nakamura et al.

- 2011 | Data quality 2 - Minoche et al.

- 2011 | Illumina pitfalls - Kircher et al.

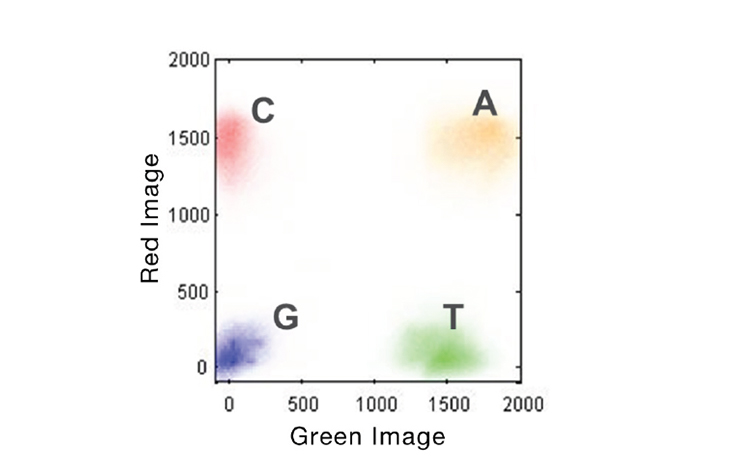

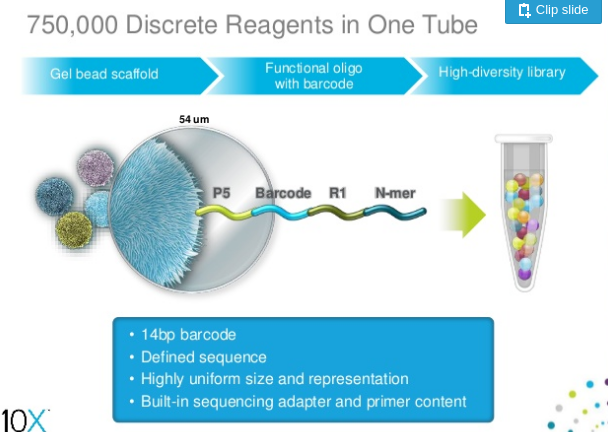

10X: A way to extend the utility of short Illumina reads

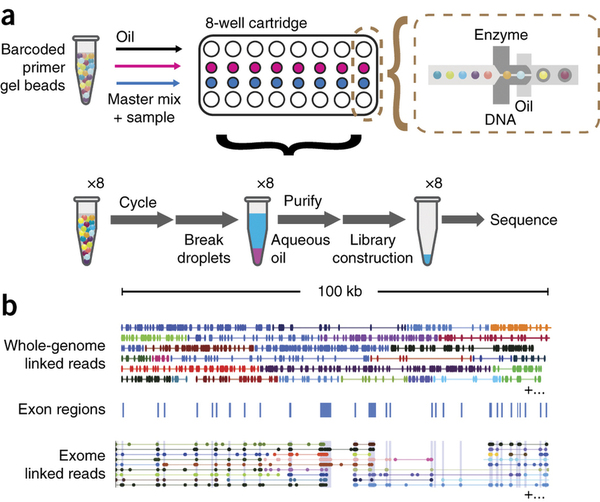

A company called 10X Genomics has developed a technology which labels reads derived from continuous fragments of genomic DNA. In this technology a gel bead covered with a large number of adapter molecules is placed within a droplet containing PCR reagents and one or several long molecules of genomic DNA to be sequenced.

|

| 10X bead containing the standard Illumina P5 adapter combined with barcode, sequencing primer annealing site (R1) and random primer (N-mer) Slide from Slideshare. |

The droplets are generated by combining beads, PCR reagents, and genomic DNA in a microfluidic device:

|

| 10X workflow (a) Gel beads loaded with primers and barcoded oligonucleotides are mixed with DNA and enzyme mixture then oil-surfactant solution at a microfluidic ‘double-cross’ junction. Gel bead–containing droplets flow to a reservoir where gel beads are dissolved, initiating whole-genome primer extension. The products are pooled from each droplet. The final library preparation requires shearing the libraries and incorporation of Illumina adapters. (b) Top, linked reads of the ALK gene from the NA12878 WGS sample. Lines represent linked reads; dots represent reads; color indicates barcode. Middle, exon boundaries of the ALK gene. Bottom, linked reads of the ALK gene from the NA12878 exome data. Reads from neighboring exons are linked by common barcodes. Only a small fraction of linked reads is presented here. Reproduced from Zheng:2015 (click the image to go to the original paper). |

In essence, 10X allows to uniquely map reads derived from long genomic fragments. This information is essential for bridging together genome and transcriptome assemblies as we will see in later in this course.

PacBio Single Molecule Sequencing

PacBio is a fundamentally different approach to DNA sequencing as it allows reading single molecules. Thus it is an example is so called Single Molecule Sequencing or SMS. PacBio uses highly processive DNA polymerase placed at the bottom of each well on a microtiter plate. The plate is fused to the glass slide illuminated by a laser. When polymerase is loaded with template it attracts fluorescently labeled nucleotides to the bottom of the well where they emit light with a wavelength characteristic of each nucleotide. As a result a “movie” is generated for each well recording the sequence and duration of incorporation events. One of the key advantage of PacBio technology is its ability to produce long reads with ones at 10,000 bases being common.

Slides

And another set of slides from @biomonika:

Video

Underlying slides are here

Reading

- 2015 | Resolving complex regions in Human genomes with PacBio - Chaisson et al.

- 2014 | Transcriptome with PacBio - Taligner et al.

- 2012 | Error correction of PacBio reads - Koren et al.

- 2010 | Modification detection with PacBio - Flusberg et al.

- 2009 | Real Time Sequencing with PacBio - Eid et al.

- 2008 | ZMW nanostructures - Korlach et al.

- 2003 | Single Molecule Analaysis at High Concentration - Levene et al.

Oxford Nanopore

Oxford nanopore is another dramatically different technology that threads single DNA molecules through biologically-derived (transmembrane proteins) pore in a membrane impermeable to ions. It uses a motor protein to control the speed of translocation of the DNA molecule through membrane. In that sense it is not Sequencing by synthesis we have seen in the other technologies discussed here. This technology generates longest reads possible today: in many instances a single read can be hundreds of thousands if nucleotides in length. It still however suffers from high error rate and relatively low throughput (compared to Illumina). On the upside Oxford Nanopore sequencing machines are only slightly bigger than a thumb-drive and cost very little.

Slides

A recent overview of latest developments at Oxford Nanopore can be found here as well as in the following video

Reading

- 2018 | Comparison of Oxford Nanopore basecalling tools

- 2017 | The long reads ahead: de novo genome assembly using the MinION

- 2016 | The promises and challenges of solid-state sequencing

- 2015 | Improved data analysis for the minion nanopore sequencer

- 2015 | MinION Analysis and Reference Consortium

- 2015 | A complete bacterial genome assembled de novo using only nanopore sequencing data

- 2012 | Reading DNA at single-nucleotide resolution with a mutant MspA nanopore and phi29 DNA polymerase

- Simpson Lab blog

- Poretools analysis suite

- Official Nanopore videos

Other weird stuff

There were of course other sequencing technologies. Most notably SOLiD, Complete Genomics, and Ion Torrent. The slides below briefly summarize these:

Reading

- SOLiD | A high-resolution, nucleosome position map of C. elegans reveals a lack of universal sequence-dictated positioning

- Complete Genomics | Human genome sequencing using unchained base reads on self-assembling DNA nanoarray

- Ion Torrent | An integrated semiconductor device enabling non-optical genome sequencing